We did a bunch of hiking while staying in Frederick, MD for a couple of weeks on our 50 state road trip, but we also did a couple of Civil War-related activities while there.

The first was a visit to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine which can be found in downtown Frederick, a cute part of town. We weren’t sure beforehand how interesting it would be; as it turns out – very interesting!

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine is surprisingly spacious inside, with exhibits on two floors. You buy your tickets on the first floor, then head up to the second floor which is where the exhibits begin.

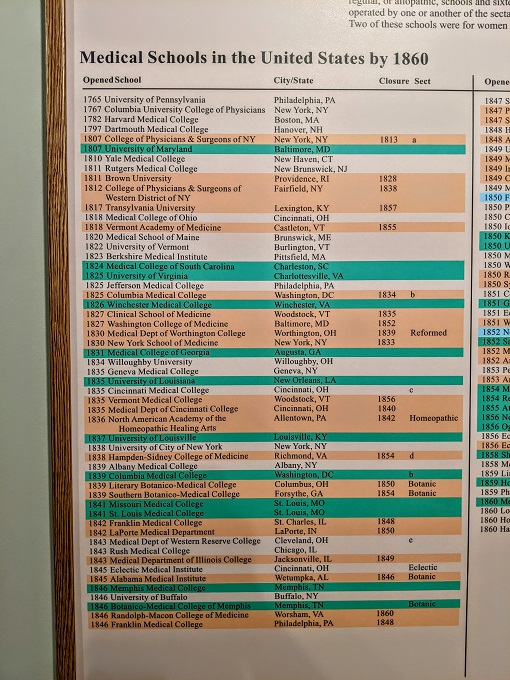

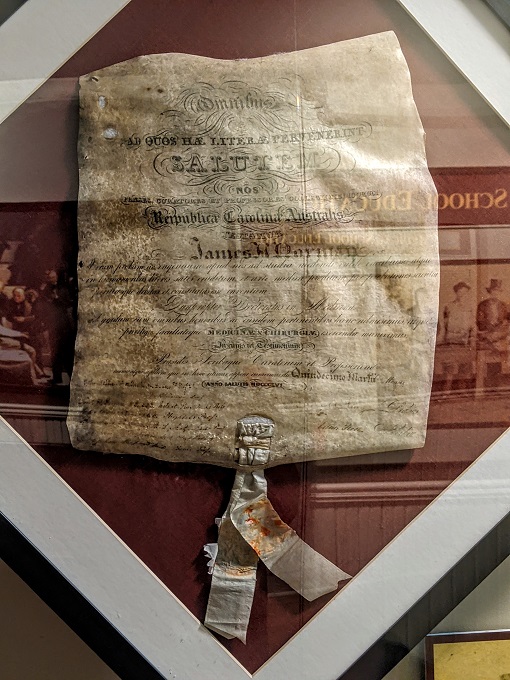

The first part of the museum looks at general medical history as medical knowledge still wasn’t particularly advanced when the Civil War started. Having said that, there were still numerous medical schools where you could learn and receive qualifications.

There was also a replica of a painting by Robert Hinckley called The First Operation Under Ether. This painting depicted the first public demonstration of sulfuric ether being used as an anesthetic which took place on October 16, 1846. The patient in the painting was having a small tumor removed from his jaw.

Having discovered how sulfuric ether and chloroform could be used as anesthetics, their usage became far more widespread. As a result, 95% of surgeries in the Civil War used anesthesia.

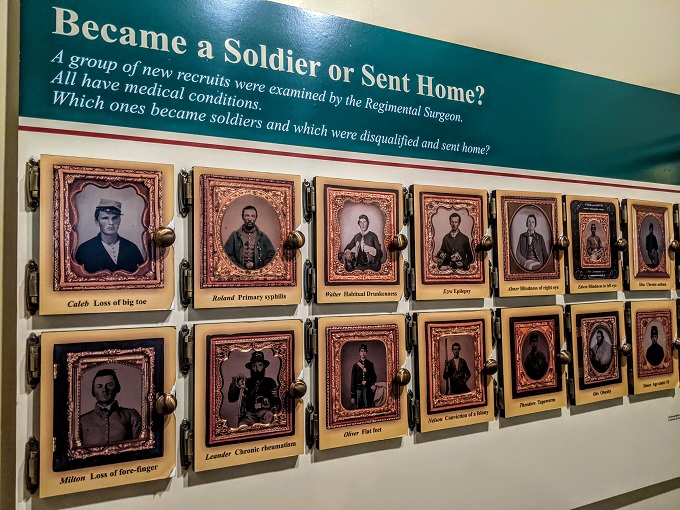

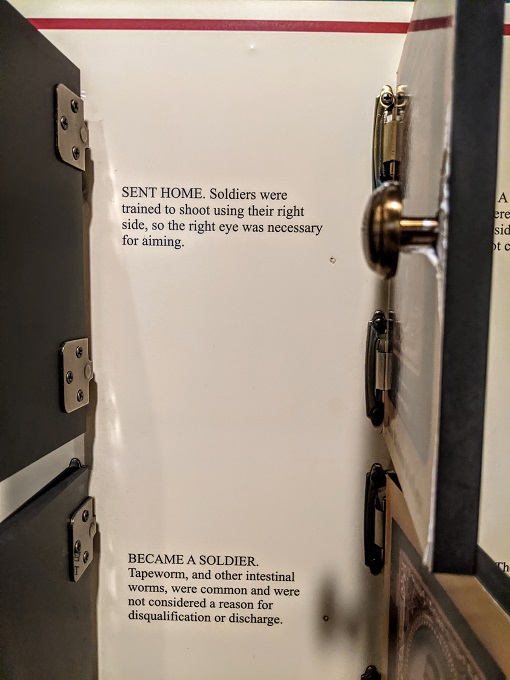

There are several interactive exhibits at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. The one below had more than a dozen photos of recruits in the Civil War. Each of them had some kind of ailment such as loss of a big toe or loss of sight in one eye; your task is to work out whether or not they’d have been sent home by the Regimental Surgeon.

Some of the results were a little surprising. For example, if you had blindness in your right eye you were sent home because the right eye was deemed necessary for aiming, but if you were blind in the left eye you could stay. Similarly, if you had early stage syphilis you were allowed to stay.

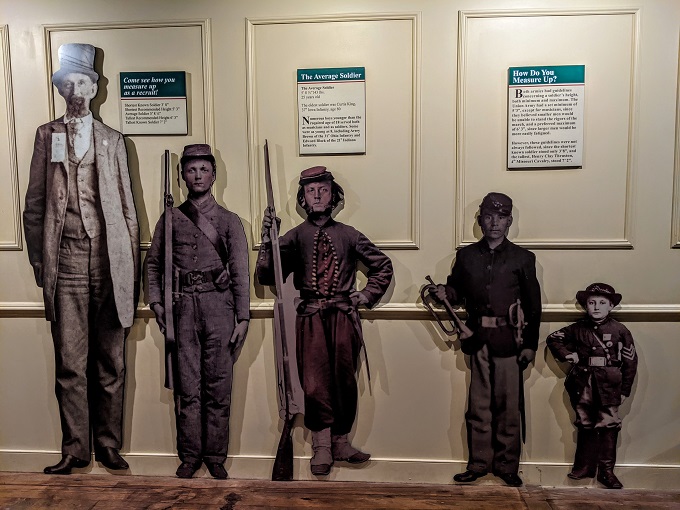

Height could also prove to be an issue. The Union Army set a minimum height of 5′ 3″ and maximum height of 6′ 3″. That’s because they were concerned shorter soldiers would have a hard time dealing with all the marching, while taller soldiers would get tired more easily.

Despite that, the tallest known soldier – Henry Clay Thruston – was 7′ 2″, while the shortest known soldier was 3′ 8″.

Before the Civil War, there wasn’t any kind of organized system to transport injured soldiers from the battlefield to the hospitals set up at the rear.

On August 2, 1862, a Union General by the name of George B. McClellan authorized Dr Jonathan Letterman to set up a new ambulance system. As a result, each regiment of the Army of the Potomac received three ambulances – one four-horse and two two-horse ambulances. Each ambulance had a driver, two litters and two people to help the wounded. Other men were tasked with being stretcher-bearers to carry the wounded from the battlefield.

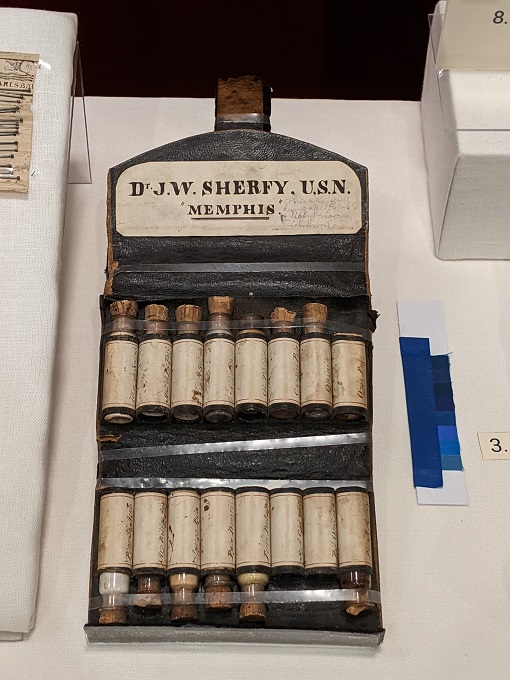

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine has a lot of artefacts from the Civil War, such as these patent medicines.

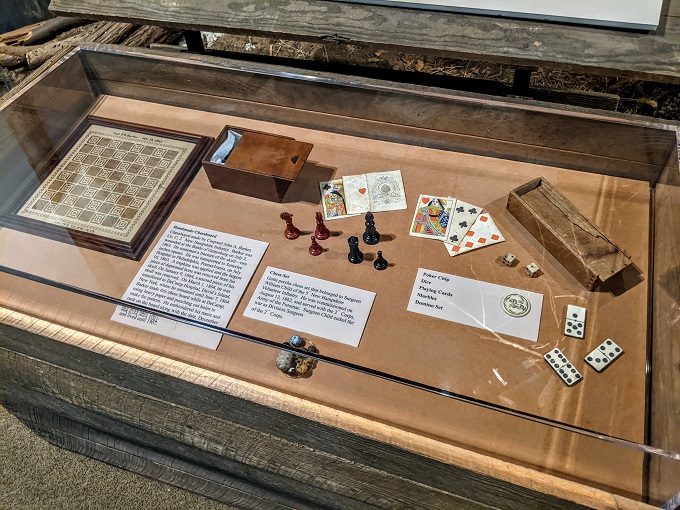

Another exhibit featured games that the soldiers would have played while not on the battlefield.

The item on the left in the above photo is a handmade chessboard. It was made by Corporal John A. Barker while he was being treated at DeCamp Hospital in New York in 1864 and was made using heavy paper and by punching out holes to make the pattern. I can’t even imagine how much patience and precision was involved in constructing that chessboard!

An exhibit which was particularly cool was the wall-tent below as it was an actual wall-tent used in the Civil War. It belonged to Surgeon John Wiley of the 6th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry; their regiment took part in the Battle of Gettysburg among others.

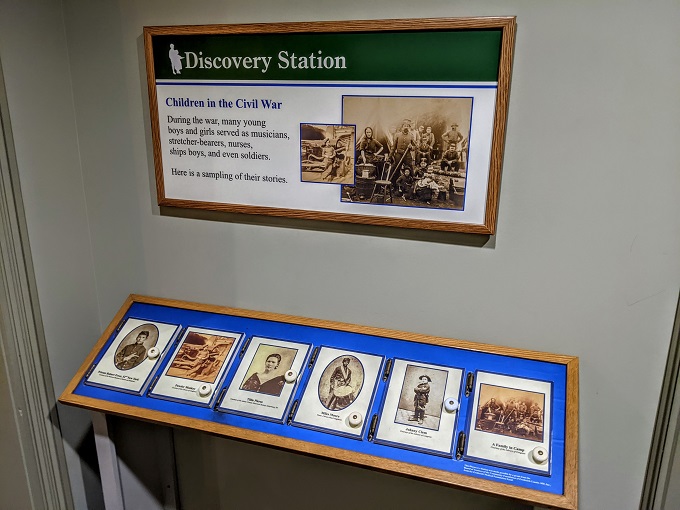

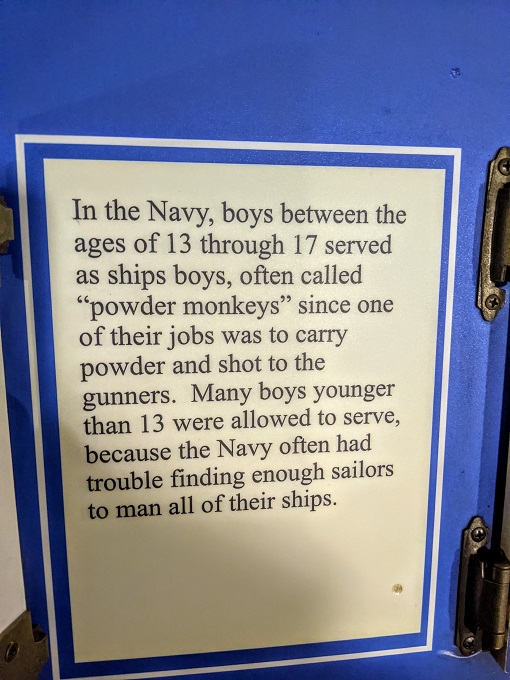

Another interactive exhibit featured stories of roles children played during the Civil War, such as being powder monkeys.

The museum also has several recreations of scenes relating to Civil War medicine, such as the one below featuring a Field Dressing Station.

There was a section of the museum relating to amputations too. This recreation featured a pine kitchen table which was actually used as a makeshift operating table back in the day and still has blood stains on it.

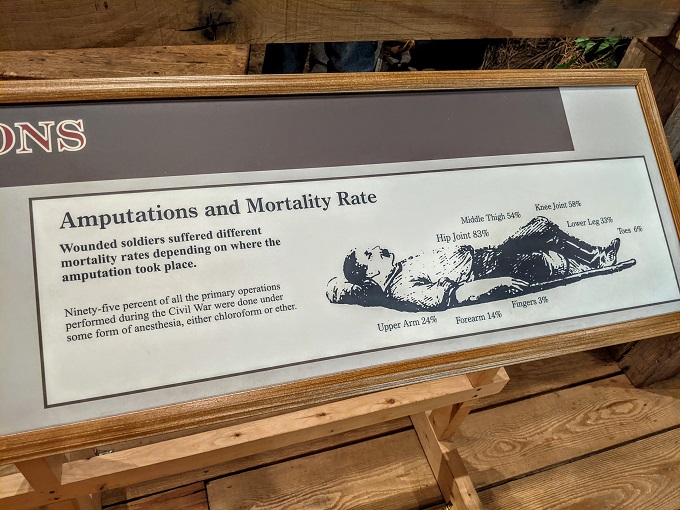

Many amputations were conducted due to injuries received during battles, with your risk of dying varying depending on what was amputated. Just in case the text in the photo below is too small for you to see, here are the various mortality rates depending on where the amputation took place:

- Hip joint – 83%

- Knee joint – 58%

- Middle thigh – 54%

- Lower leg – 33%

- Upper arm – 24%

- Forearm – 14%

- Toes 6%

- Finger 3%

While a 3% mortality rate for a finger amputation seems good in comparison to some of the other body parts, that’s still very high considering the fact that it shouldn’t be deadly; deaths from finger amputations presumably came about as a result of subsequent infections.

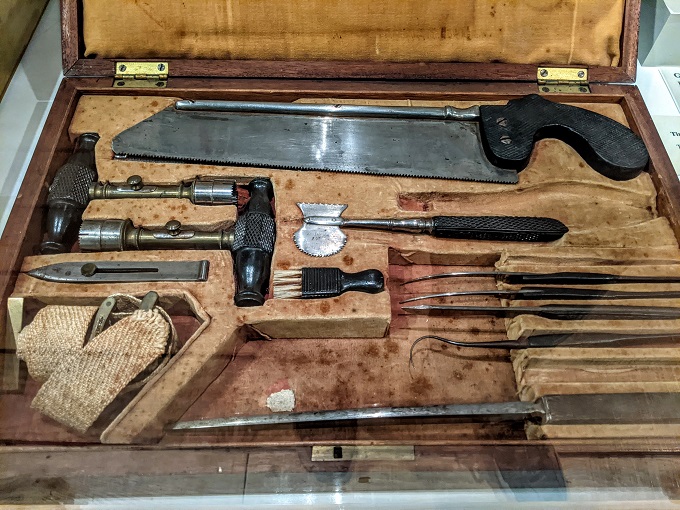

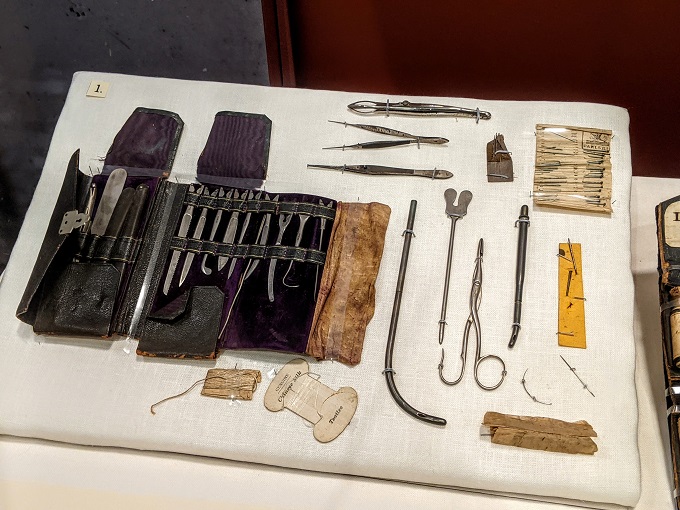

The amputation kit looked like something out of a horror movie. All it needed was a creepy mask and a meathook.

One of the most well-known exhibits at the National Museum Of Civil War Medicine is the Antietam Arm. The arm was found on the Antietam battlefield and is thought to have been found near Burnside Bridge soon after the battle in 1862.

It’s believed the arm belonged to a 16-18 year old male. The creepiest aspect is that it wasn’t amputated – it was torn from the body at the elbow joint at or near the time of death. Try not too think for too long about what would’ve caused that to happen.

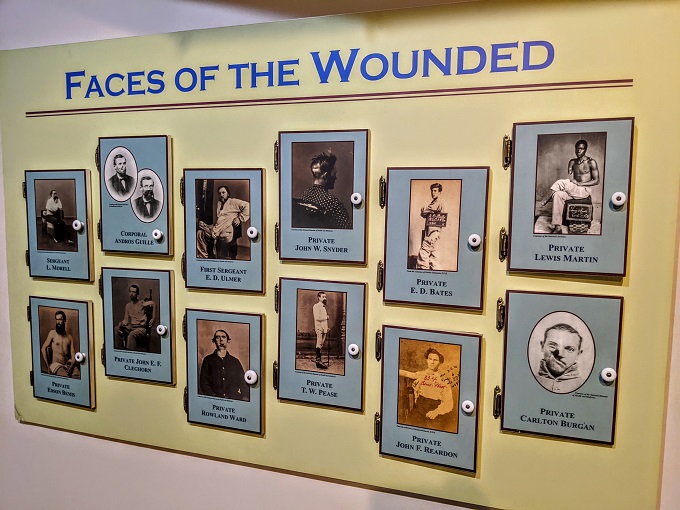

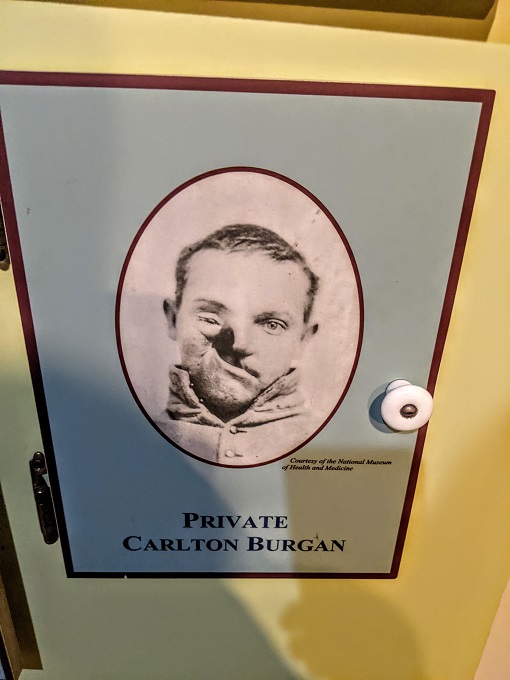

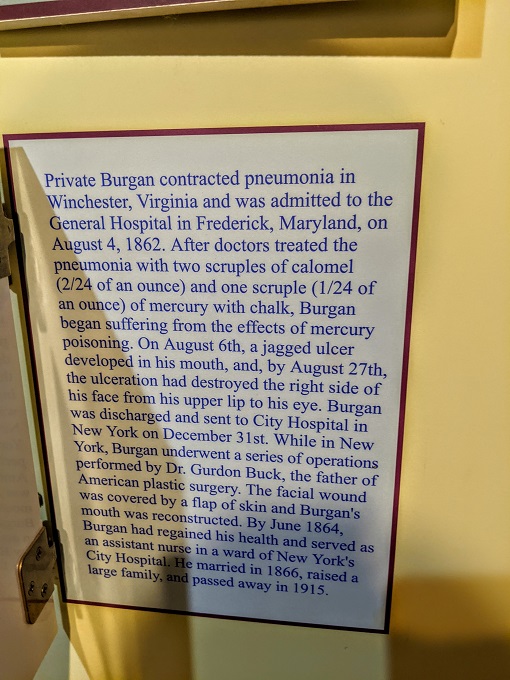

Another somewhat creepy exhibit was Faces Of The Wounded which featured a dozen photos of soldiers who suffered injuries during the Civil War.

Behind the doors were stories of what happened to each of them.

There was so much to see and learn at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, with all kinds of historical artefacts on display.

Another recreation featured hospital stewards with information boards providing details about the role they played. In the photo below, you can see pine branches draped from the ceiling. That wasn’t only done for decoration but also to help freshen the air in the hospital.

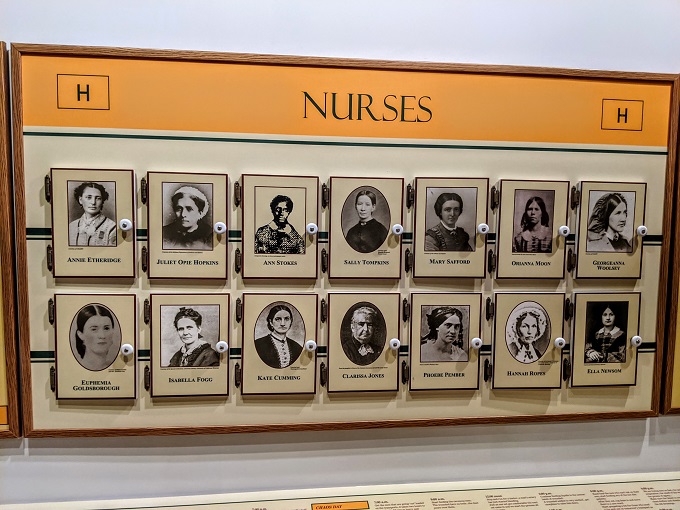

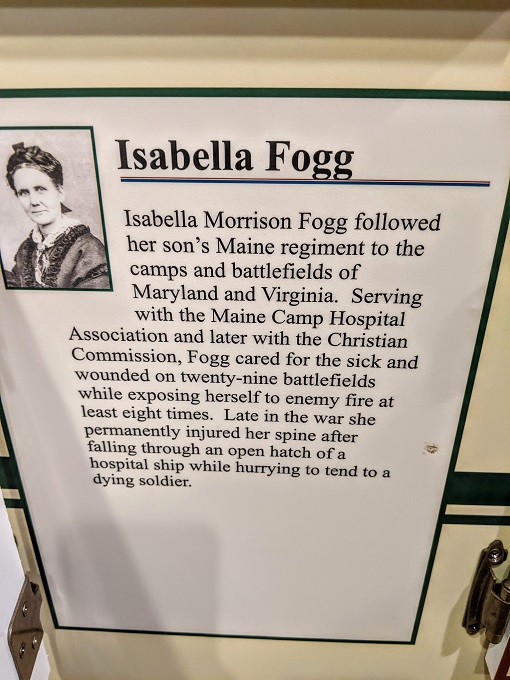

That same area had information about the role nurses played in the Civil War, including stories of some specific nurses.

Even though the medical field wasn’t anywhere near as advanced back then as it is now, it was surprising how similar some aspects were such as the wheelchair below from the 1870s.

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine has a replica Autenrieth wagon which represented a huge advance in wartime medicine. Before this was designed, medicine was carried in trunks and large chests on wagons, but medicine bottles often arrived broken seeing as they weren’t packaged properly.

The design of the Autenrieth wagon and the way medicine was stored in it meant they arrived in much better condition. The wagon also had sliding shelves and drawers, as well as a flat work surface. This was such a huge development that after the Civil War ended, the Union Medical Department regarded the Autenrieth wagon as one of its greatest accomplishments.

The wagon helped improve transportability of medicine on the battlefield. Another way surgeons were able to quickly treat injured soldiers was by carrying pocket surgical and apothecary kits.

One of the final exhibits at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine was a holding coffin from the mid-1800s. Undertakers didn’t have as many options then as they do now, so holding coffins such as this were used to help temporarily preserve bodies.

The coffins contained metal trays above and below the bodies, with ice placed inside to help preserve it. These holding coffins were used for displaying bodies, but they’d then be moved to a permanent coffin before being buried.

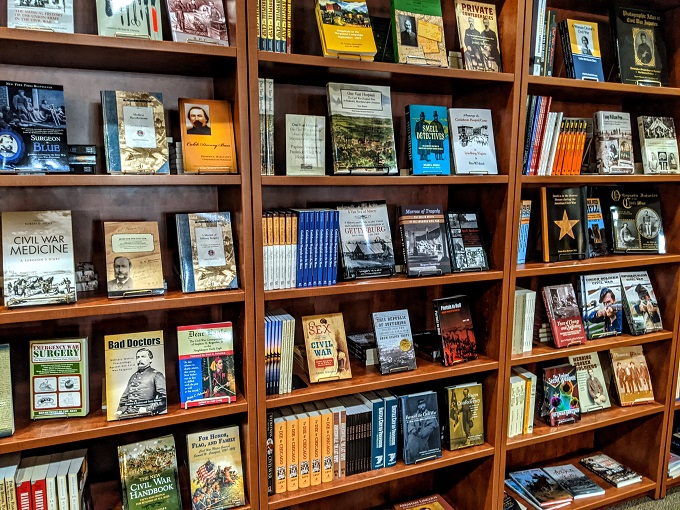

Needless to say, you exit the museum through the gift shop. There’s all kinds of stuff on sale, with a wide selection of Civil War-related books available among other items.

Final Thoughts

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine was even more interesting than we were expecting it to be. We’ve visited a number of Civil War museums and locations on our road trip, but looking at it through the lens of medicine gave us a new take on what life was like, not only for injured soldiers but for those treating them too.

If you’re visiting Frederick, MD, we’d definitely recommend taking a couple of hours to visit this museum.

Ticket Prices

At the time of our visit in October 2020, here were the ticket prices:

- Adults – $9.50

- Seniors (65+) – $8.50

- Students – $7.00

- Military (with ID) – $8.50

- Members – Free

- Children (9 and under) – Free

Address

National Museum Of Civil War Medicine, 48 E Patrick St, Frederick, MD 21701

Thanks for your review. I’ve been to Frederick several times, but have not yet visited this museum. Next time!

It’s definitely worth a visit!