Did you know that there’s a Fort Knox in Maine?

It’s not the Fort Knox (that’s in Kentucky), but the one in Maine is named after the same person. Major General Henry Knox was the first Secretary of War in America and the Commander of Artillery during the American Revolution and lived in Maine towards the end of his life.

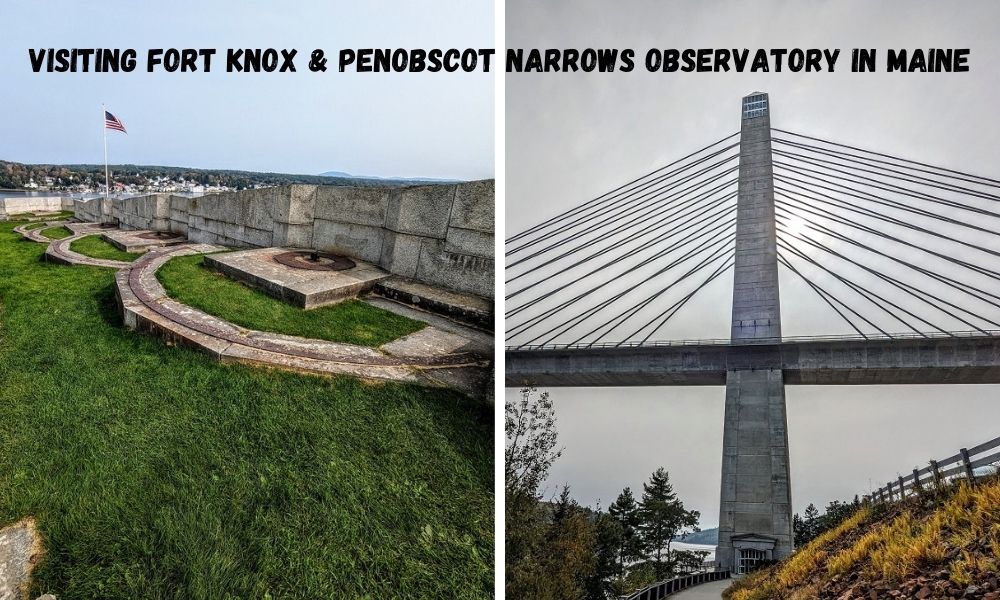

The fort named after him in Maine is about 30 minutes south of Bangor, so we paid it a visit while staying near there. It was an interesting place to visit, especially because right next to the fort is a somewhat new bridge which has the tallest public bridge observatory in the world – the Penobscot Narrows Bridge Observatory.

Here’s more about the two locations.

Fort Knox State Historic Site

We started off at Fort Knox State Historic Site. We’d bought a Maine State Park pass the previous week which meant that we were able to get free entry to Fort Knox.

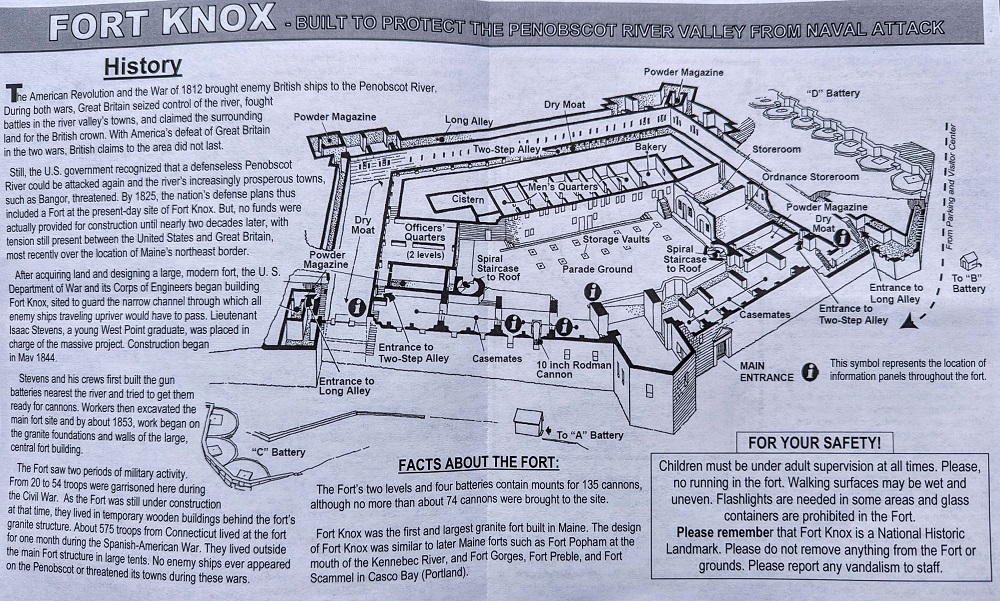

When arriving we were given an information sheet about the site which included a map of the fort.

We started off by visiting the Visitor & Education Center which had boards providing more information about what led to the fort being built, its construction and what it was used for.

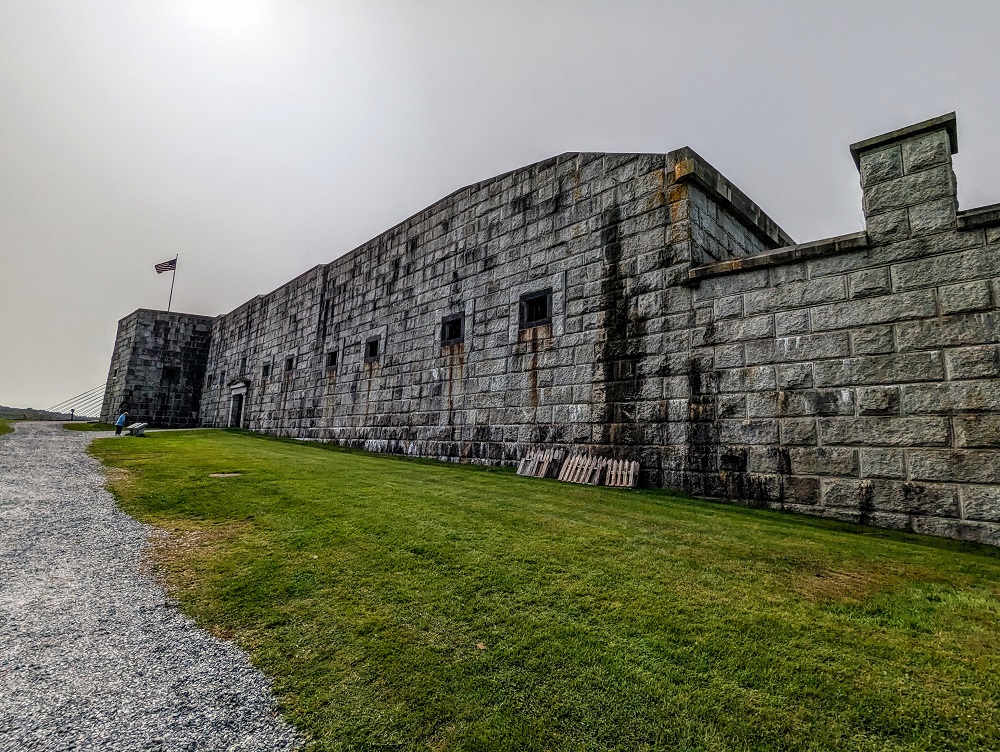

From there we headed outside to explore the fort. The pentagon-shaped Fort Knox was built using granite from nearby Mount Waldo and was the first fort in Maine to be built using this material.

The fort was built due to concerns about Great Britain. Despite beating them in the American Revolution and War of 1812, there were fears that the British would once again try to gain control of the Penobscot River, especially considering Maine’s proximity to Canada.

Despite a push to have a fort built on the site, construction didn’t begin until 1844 and continued for about 25 years. Ultimately, the fort never saw any battle action due to developments in war weaponry in a couple of regards. One is that the cannons that were due to be used at Fort Knox became outdated with the advent of ironclad ships in the Civil War. The other is that more sophisticated weaponry meant that the fort’s granite walls were no longer as impenetrable as they had been decades before its construction. New rifled cannons were more accurate and forceful than previous cannons and were capable of demolishing the fort’s thick granite walls.

The fort has multiple levels that you can explore. We started off on the main level, checking out some of the casemates.

Casemates are enclosed spaces within a fort that have arched ceilings and small windows through which cannons can fire. This design helped protect both the cannons and soldiers inside from enemies on the outside.

The high ceilings, open space at the back and vents in the ceiling helped ensure smoke from the cannons dissipated more easily while also reducing some of the noise from the cannons.

Some of the casemates had additional exhibits such as an old ambulance and examples of cannons that would’ve been used here.

Despite never seeing any action and never being fully fortified with all of the 135 cannons it was capable of holding, Fort Knox was stocked with some cannons. Some of those were 24-pounder Flank Howitzers. The 24-pounder weight refers to the weight of the canister shot that was loaded into the cannon. This was a tin can filled with iron or lead balls that, when shot, would send those balls at the enemy, increasing the likelihood that each shot could take out multiple opposing soldiers or cause widespread damage of ships that it was shooting at.

The cannons were loaded on to wheeled mounts that were themselves sitting on a curved metal railing to allow its operators to maneuver it back and forth depending on where it needed to be aimed.

In the center of the fort was a large grassy area. This was used as a parade ground where drills would be conducted. Towards the back of the photo below you can see two rows of squares on the ground with circular sections in the middle of them. These were holes in the ground used as food storage bins as well as for storing fuel.

After exploring some of that level, we walked up one of the two sets of spiral staircases.

You can then walk around on the grassy roof which is called a terreplein. There was space up there for 30 cannons which represented almost a quarter of the fort’s potential firepower. However, the fort only ever received 74 cannons (out of a potential 135), so the terreplein never had any cannons mounted as the other batteries and casemates proved to be a higher priority.

From up there you get a good view of the Penobscot River, as well as the parade ground below.

One of the things we liked about visiting Fort Knox is that it’s pet-friendly. I visited Fort Knox with my parents one day while Shae was working, then we returned there a few days later as I knew Shae would want to check it out and we brought Truffles along with us.

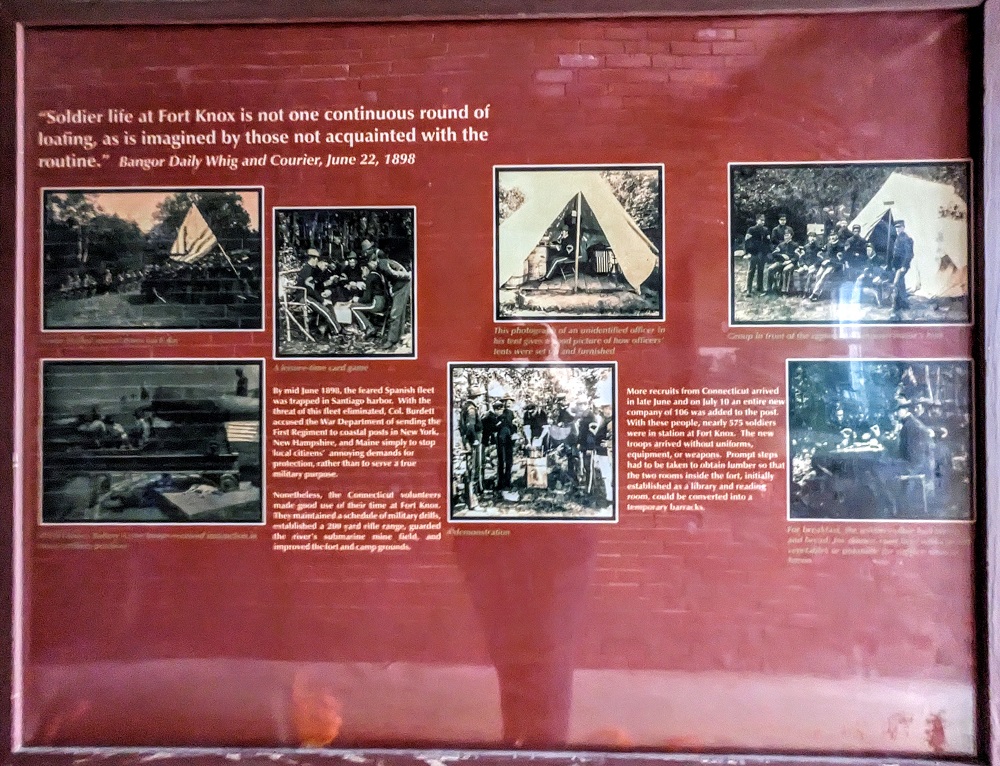

After walking around on the roof, we headed back down to the main level where we continued looking around that area. There were additional exhibits, including some information boards featuring photos taken at Fort Knox in the late 1800s.

One of the areas of the fort I found most interesting was its bake house.

The reason I found it so interesting was due to the scale of the operations in this room. The oven was 10 feet wide, 15 feet deep and was capable of baking almost 400 loaves of bread at a time. That much bread was needed because soldiers had a ration of 1.5 lbs of bread per day.

The oven had a large fire lit inside it each morning which would burn for several hours. Once the bricks lining the oven were sufficiently hot, the coals were removed; the oven then stayed hot enough to bake bread for 6-8 hours.

To the right of the oven was a large space used as a drying room. This is where wood was placed to dry it out before it was used to heat the oven.

Having walked around the main fort area, we walked outside of that space and made our way towards what looks like a nondescript white hut but which is in fact a stairway down to the B Battery.

The first time we visited Fort Knox this passageway wasn’t lit up and so we had to use the flashlights on our phones to make our way down. The second time we visited the lights were turned on, so I’m not sure why it was so dark during that first visit.

Battery B was constructed in 1845 with placings for 15 cannons but none were received. 16 years later the Civil War began, yet there were still no cannons for Battery B, nor Battery A. The government of Maine pushed the Department of War to supply Fort Knox with cannons, but due to the years upon years of delays, there was a problem.

Battery B had been built to accommodate 32-pounder cannons. However, by the time cannons were going to be sent to Fort Knox, 10-inch Rodman cannons were in use. 10-inch Rodman cannons are more powerful than 32-pounders, so the supervising engineer of the site and his crews had to spend months reinforcing the emplacements where the cannons would be located.

It wasn’t until 1863 that the fort received its first cannons – a couple of 10-inch Rodman cannons. Half a dozen more were added by 1866, along with a 15-inch Rodman cannon. That 15-inch Rodman cannon is all that remains at the site as the other cannons were salvaged for their parts during World War II.

This cannon was enormous. To give you a sense as to its size, here’s Shae standing behind it.

Although I found the bake house area to be interesting, the most fascinating part of the fort for me was the hot shot furnace.

Like many other parts of Fort Knox, this feature never ended up being used. It was built for the 32-pounder cannons that were originally due to be sent to the fort.

At the end of the furnace is where a fire would be built. When it was hot enough inside, fireballs would be rolled down from the higher end of the furnace.

Once they’d rolled to the end, the cannonballs would be heated by the fire for about 30 minutes until red hot. Soldiers would then remove the cannonballs using iron forks, scrape them to remove scale that would’ve attached itself during the heating process and then carried the balls over to the cannons using ladles made of iron or wood.

The reason the cannonballs would be heated is to hopefully set ships on fire when hitting them. However, by the time Fort Knox had cannons sent to them, ironclad ships were becoming more common. As a result, fire-heated cannonballs would’ve provided little benefit, especially compared to the more powerful cannons now available, hence why the hot shot furnace was never put to use.

Here’s a video Shae recorded which shares even more about how this worked:

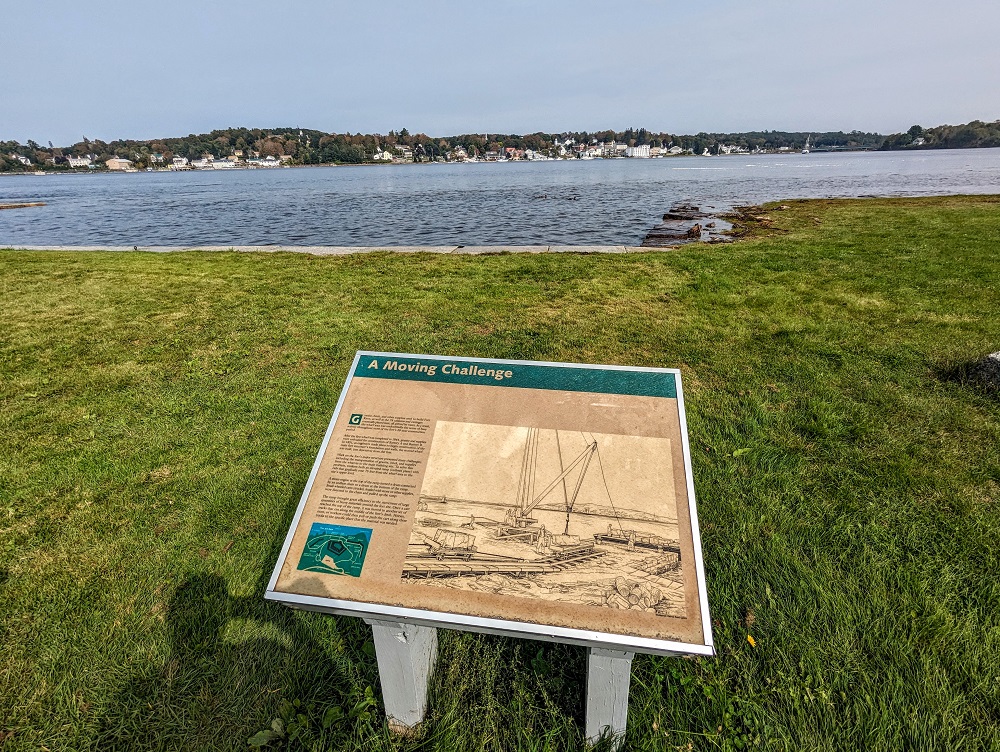

There was one final part of Fort Knox for us to check out which was on the waterfront. There wasn’t much there in terms of the fort and its defenses, but there was an information board displaying more details about how the fort was constructed.

All of the building materials and weaponry – including the giant granite blocks – were transported to the site by water. Needless to say, moving the granite blocks uphill presented logistical problems. To solve that issue, a ramp was built which had rails that rose 75 feet to the fort’s upper level. At the top of the ramp there was a steam engine which powered small carts loaded with the granite boulders or other supplies, with a chain pulling them up a ramp.

Once at the top of the ramp, the carts were pushed or pulled by oxen, horses or workers depending on how heavy the carts were laden with materials.

Fort Knox ended up being a far more fascinating place than I originally thought that it might be. That wasn’t the end of our visit though because we also visited another attraction next door – the Penobscot Narrows Observatory.

Penobscot Narrows Observatory

The Penobscot Narrows Observatory seems to be part of the same complex as Fort Knox. You can get tickets for one or the other or both. We had free entry to Fort Knox thanks to our Maine State Park annual pass, but you do have to pay to go up in the observatory. Tickets are only $2.50 though, so it’s worth the very small investment. If you’re traveling with a pup, be aware that although Fort Knox is pet-friendly, dogs aren’t allowed inside the observatory.

The Penobscot Narrows Observatory is located inside the Penobscot Narrows Bridge. The bridge opened on December 30, 2006, with the observatory opening in May 2007. The bridge replaced the old Waldo Hancock Bridge which had been built in 1931. Safety inspections revealed that the old bridge had some severe corrosion of its cables and other areas. Work was done to strengthen the Waldo Hancock Bridge temporarily, but the 2,120 foot long Penobscot Narrows Bridge was built alongside it as its replacement. It only took 42 months from conception of the new bridge to it being opened at the end of December 2006.

The Penobscot Narrows Observatory is inside one of two support towers that are modeled on the Washington Monument. At 420 feet high, it’s the tallest occupied structure in Maine and you get to visit all four levels of it. There’s the ground floor where you enter, then the elevator takes you up to a location two floors below the observatory itself. You walk up two flights of stairs which have levels along the way until you get to the top floor. If you’re not able to walk up those stairs, they do have an accessible lift available.

You’ll want to pick a good weather day to visit the Penobscot Narrows Observatory. The second time we visited, Shae missed out on going up because fog that day meant nothing could be seen from the top. My parents and I were therefore fortunate to have visited a few days beforehand when there was much better weather.

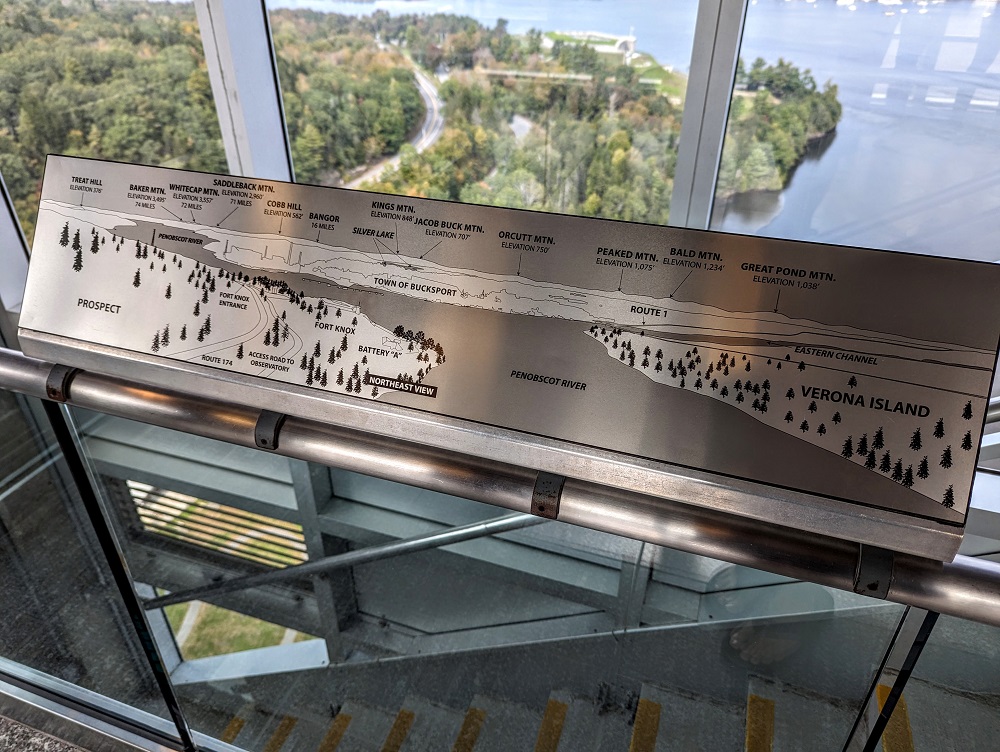

The observatory provides 360° views of the surrounding area which means you can see the bridge, the Penobscot River, Fort Knox and more.

As you can see, the observatory provides excellent views in all directions. If you’re wondering what you’re looking at, on all four sides there are maps displaying what’s out there.

Fort Knox and the Penobscot Narrows Observatory were fun and interesting places to visit – both are definitely worth checking out if you’ll have some spare time in the Bangor/Bar Harbor area.

Leave a Reply