As The Traveling Teach, I try to start my classes off with a piece of information that’s unknown, shocking or generally unbelievable.

So when I asked my students, “when I say camps in World War II, what do you think of?” they inevitably say something about the German Concentration Camps and the Holocaust. Then I say, “what if I told you we had camps here in the USA in World War II?”

Their faces are shocked. Minds. Blown.

I explain about the basics of the Japanese Interment Camps, we discuss the similarities and differences between the two camps and explore how much any of them do know about the camps in the USA that incarcerated Japanese Americans and legal residents for 3 years during the war.

Manzanar is one of ten sites around the US where 110,000 people were held prisoner in internments camps during WWII. 66,000 of them were US citizens; the others were legal residents of the US.

Their crime? Being of Japanese descent.

The US and other countries like the UK and Australia had already been building a diplomatic rift between themselves and Japan for years, particularly since World War I and creating a hostile climate for people of Asian descent in their own countries. Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens were given up to two weeks to pack up their lives and report to assembly points to be dispersed to one of ten camps around the US.

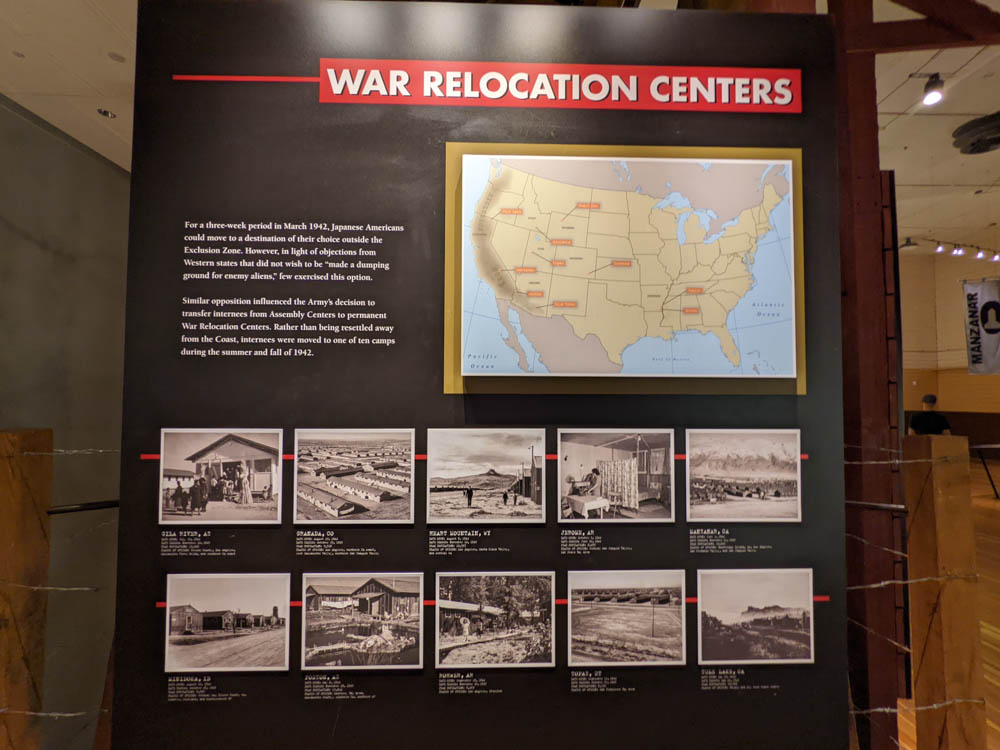

The ten War Relocation Centers were located in:

- Manzanar, CA

- Gila River, AZ

- Granada, CO

- Heart Mountain, WY

- Jerome, AR

- Minidoka, ID

- Poston, AZ

- Rohwer, AR (this was the internment camp where George Takei and his family were incarcerated)

- Topaz, UT

- Tule Lake, CA

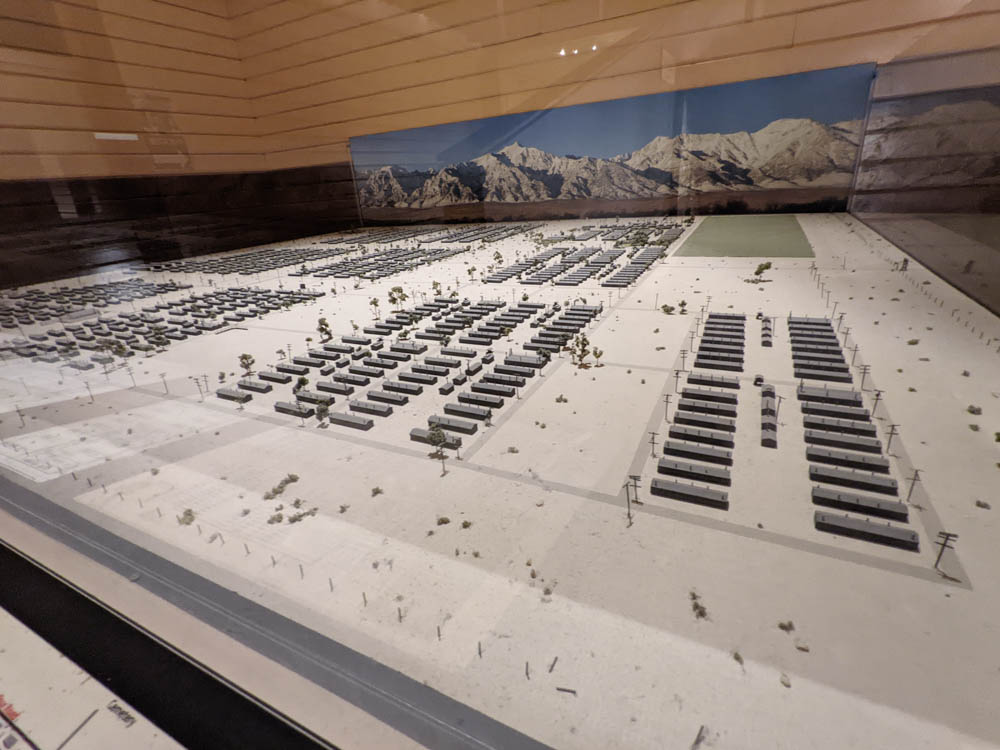

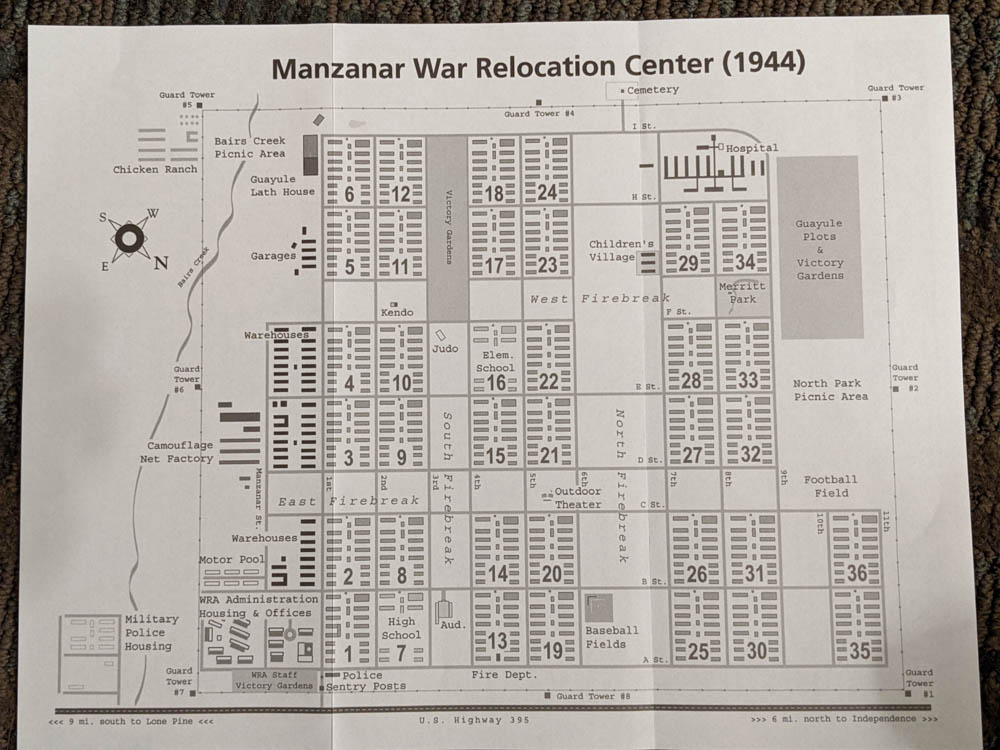

Given the barest essentials, the internees struggled to create a life for themselves and their children in the harsh desert conditions that most camps were located in.

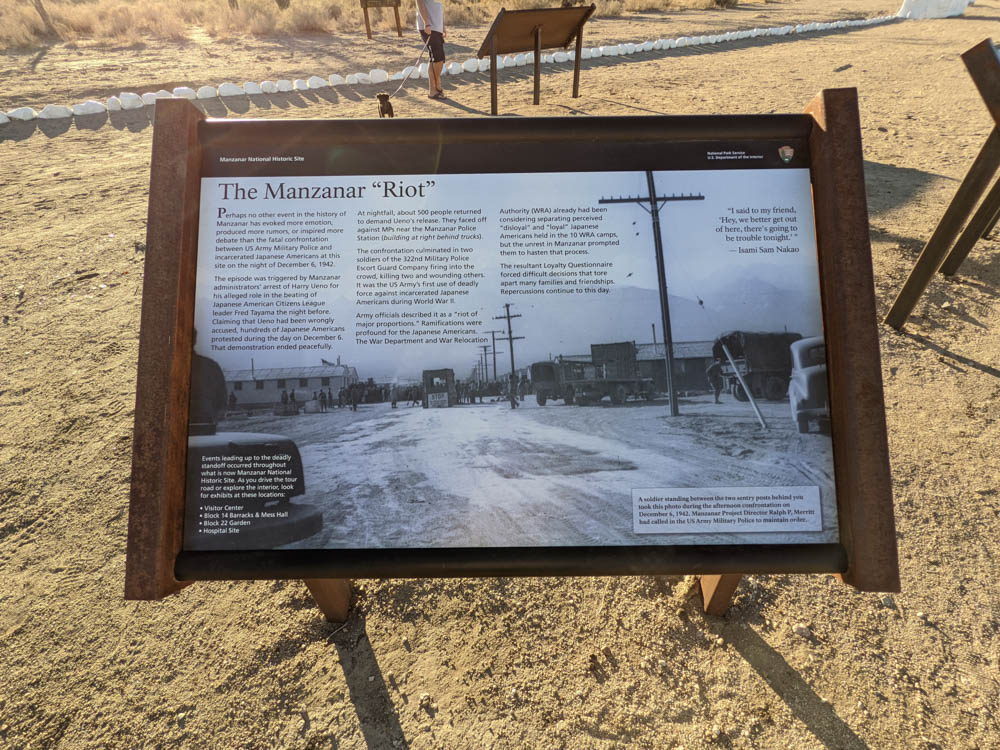

They were told that they were being moved for their safety after Pearl Harbor, but upon arriving at camps like Manzanar they found the guns pointed inward, not facing the threat from outside. They created parks and grew gardens to supplement their food rations of canned meats and bread. The children attended school, some graduating from Manzanar, but it was far from a normal childhood.

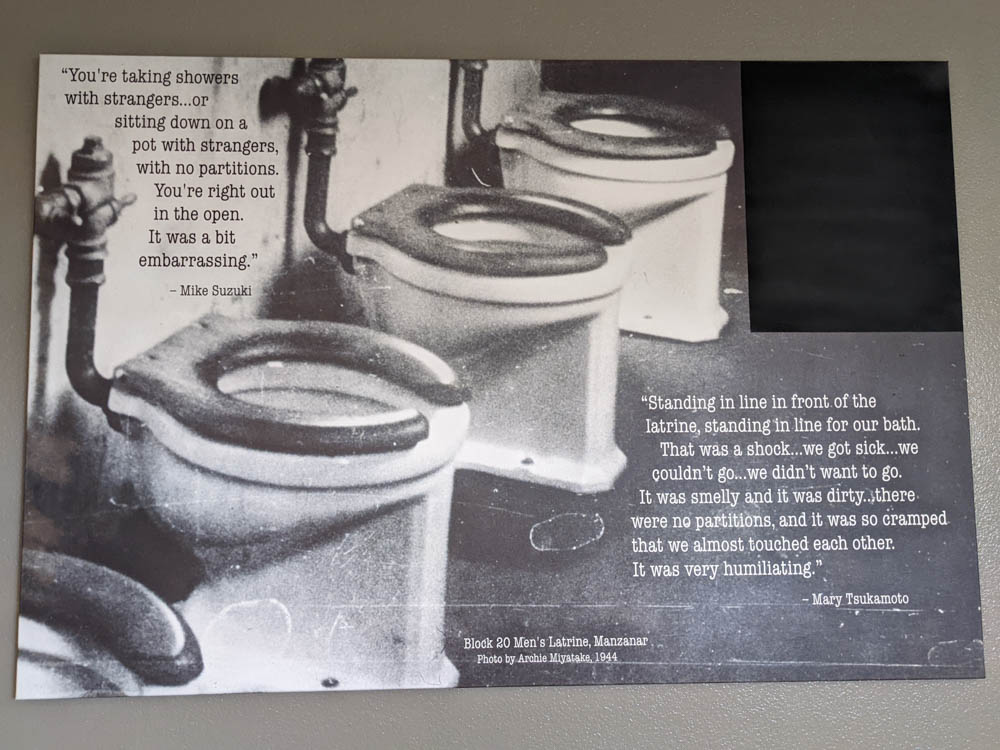

Manzanar was dehumanizing in many ways. The barrack style housing, communal toilets and showers without stalls or privacy for 10,000 people who didn’t know each other. Waiting in line for food three times a day. Hoping that you had white friends on the outside who were able to send you some of your belongings and care for your pets while you were away.

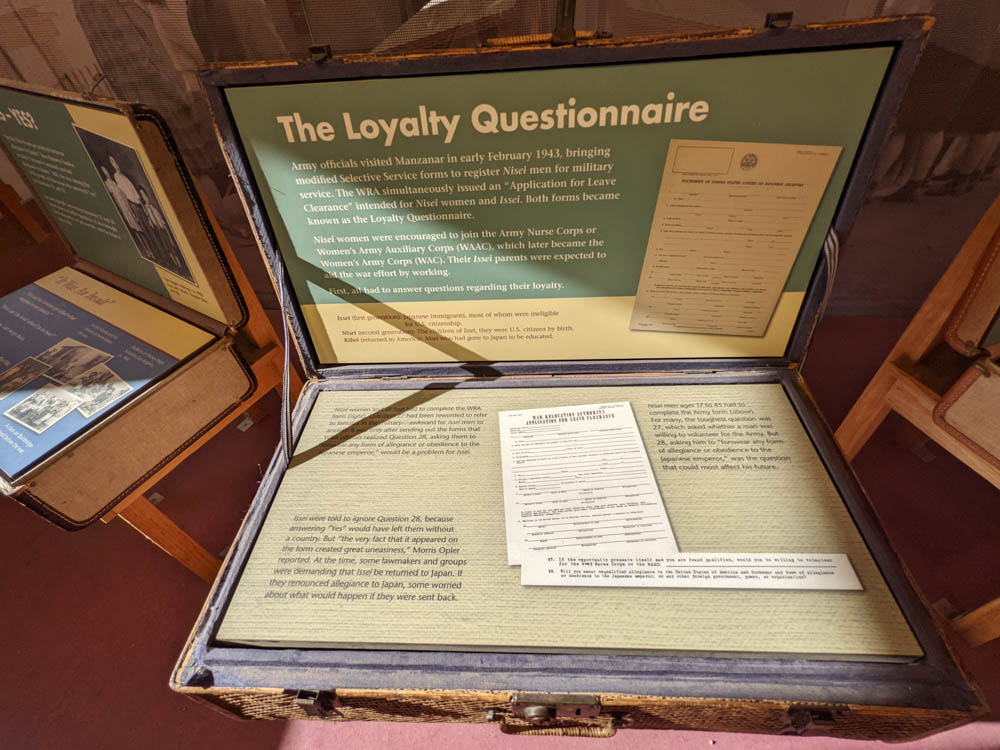

You had to prove your loyalty with the loyalty questionnaire that was provided. You had to say whether you were willing to be drafted to combat or nursing service in the military to prove your loyalty. You were asked if you’d be willing to renounce any allegiance to the Japanese Emperor. You were expected to be loyal to and supportive of the very country that locked you up (for US citizens against your rights) and took away your livelihood and homes.

Those who were merely permanent residents found the questionnaire especially hard because if they renounced Japan they’d have no country at all. Many answered “Yes, Yes” to these questions of service and loyalty while others answered “No, No” due to their complicated feelings at the time towards America. Those who answered “No, No” were often moved to another camp.

If you were lucky enough to be able to move away from Manzanar and the other camps, the requirements were that you weren’t allowed to resettle in the west – you had to head east. So your businesses, homes and possessions were all left behind to be shipped to you or lost to the government or your neighbors.

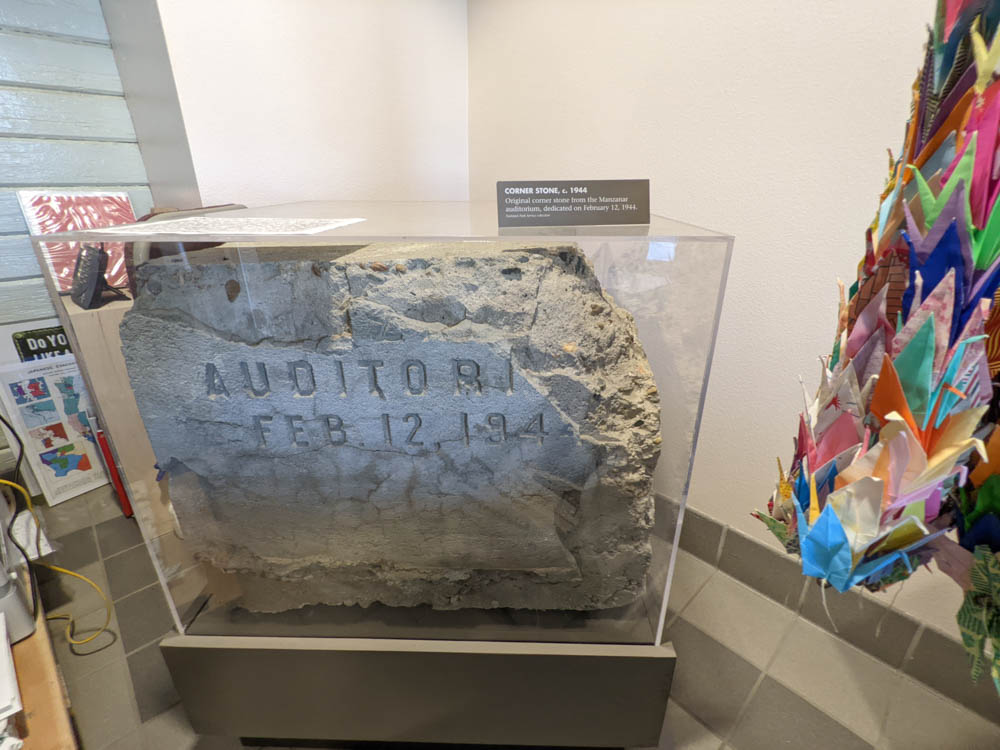

Only three of the original buildings remain at Manzanar National Historic Site, but they have the foundations of many buildings. There are roads, the cemetery and the National Park Service has recreated buildings to educate the public about life at Manzanar.

There’s the Auditorium which now houses the museum and interactive and educational exhibits, as well as the two guard buildings at the original entrance to the camp. The reconstructed buildings have videos and recordings of those who lived at Manzanar and exhibits about what life was like for those who spent three years at Manzanar.

There’s an auto tour you can take as well, driving around the entire complex of Manzanar and ending up at the far end near the cemetery for those who died while incarcerated at Manzanar.

Overall it’s an incredibly powerful place that will really open your eyes to the treatment of Japanese Americans and immigrants during WWII and helps you explore the constitutionality of the camps. The day we visited was the 80th anniversary of the Executive Order that was signed by President F. D. Roosevelt that made these camps a reality.

[…] out this post for more about this sad but important piece of US […]