“Those who would integrate our schools at any price are still among us.”

This is from the former Governor of Arkansas in 1958, after the school year in 1957 that found nine black students of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas embroiled in a year of violence, intimidation and racism because they wanted to go to an integrated public school as allowed by the US Supreme Court in 1954 with the Brown vs. Board of Education decision.

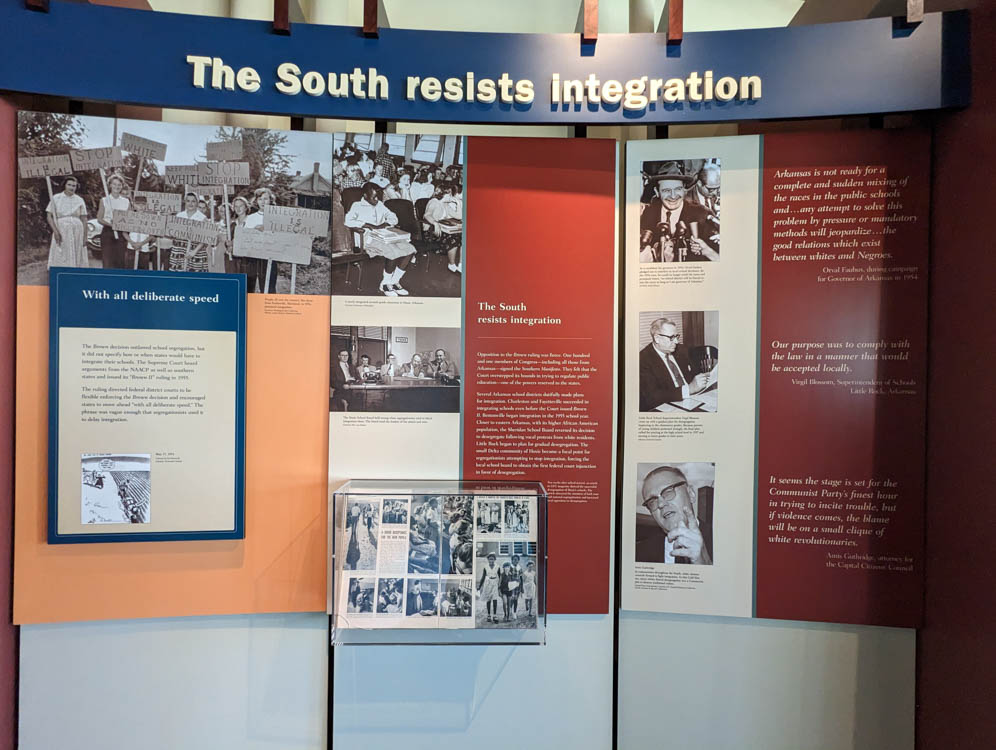

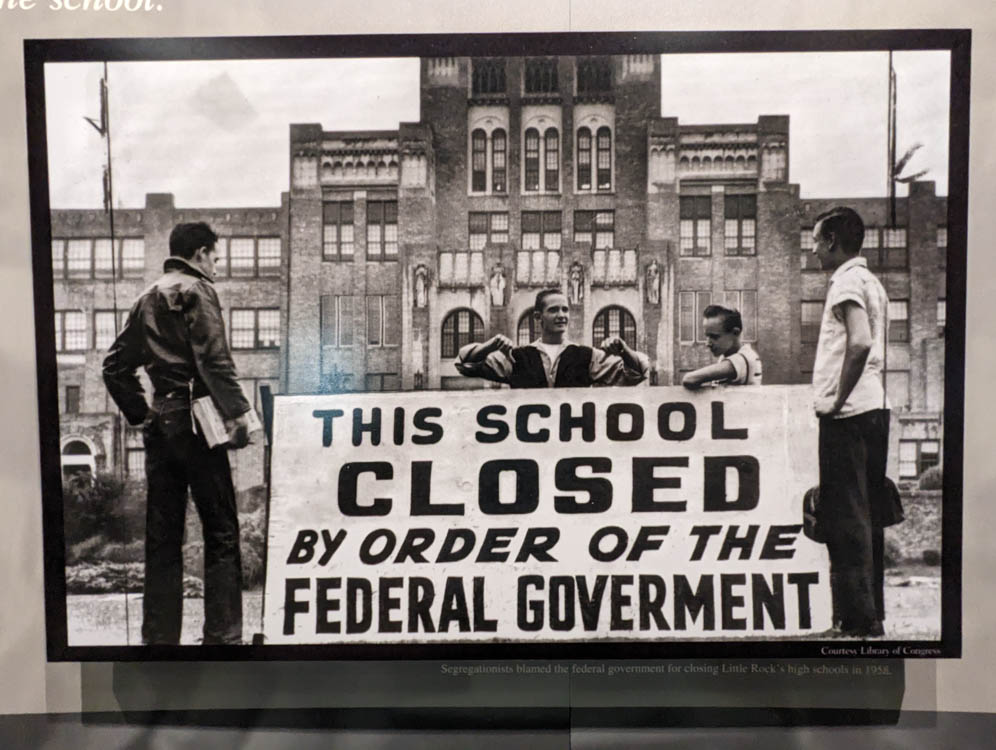

He was addressing the public vote on a decision to close Little Rock Public Schools in 1958 rather than integrate black and white students in the school district. You can read the full speech here if you’d like a masterclass in white supremacy and hate hidden amongst political rhetoric about protecting children, state rights and “big federal government.” You may find it familiar (read: practically identical) to what we’re hearing out of certain states in the US regarding the LGBTQ+ community in schools, the banning of books, the exclusion of black and indigenous history in the classroom and more right now in 2023.

Little Rock, Arkansas was the site of the Central High School and “Little Rock Nine” historic event, when nine black students tried to go to high school with white students as was their constitutional right. The museum is right across the street from the Mobil gas station, intersection and Central High School where the events of September 1957 unfolded.

The museum itself is well done and really interesting. We visited here in 2011 and remember it being incredibly powerful. 12 years later, it still is. We’ve had the opportunity to visit a lot of important historic sites for the Civil Rights Movement on our road trip and this still stands out to us as a recommended stop when you’re traveling through Arkansas.

You can take guided tours by the National Park Service into the school as well. However, we were there at the weekend and so we only saw the museum and the outside of the school which is still an operating public high school.

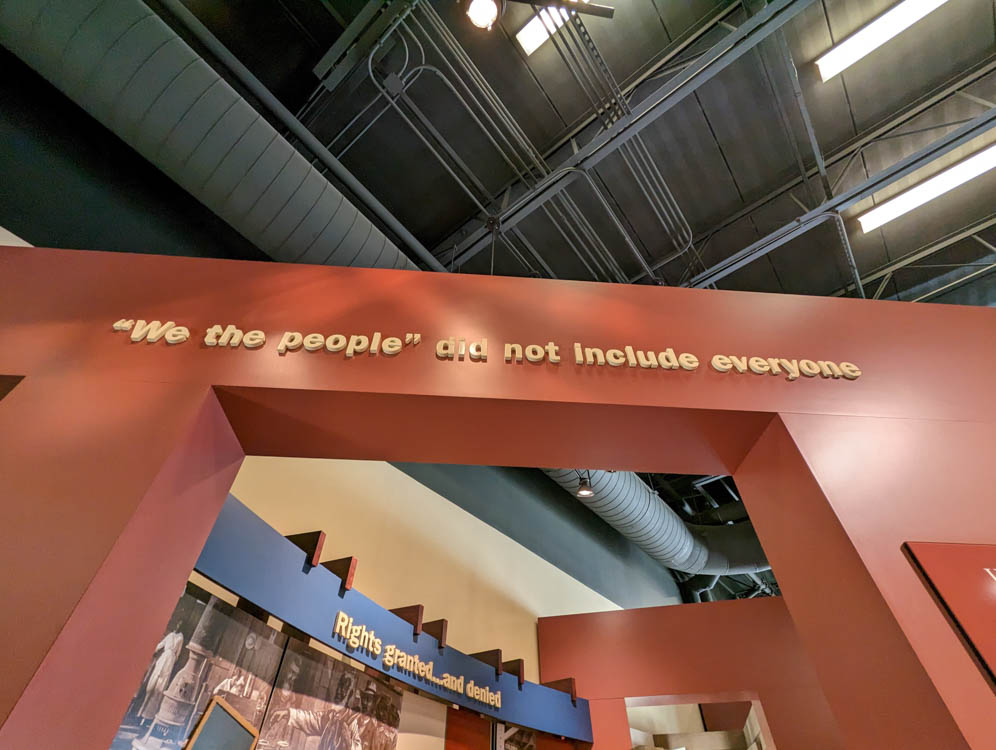

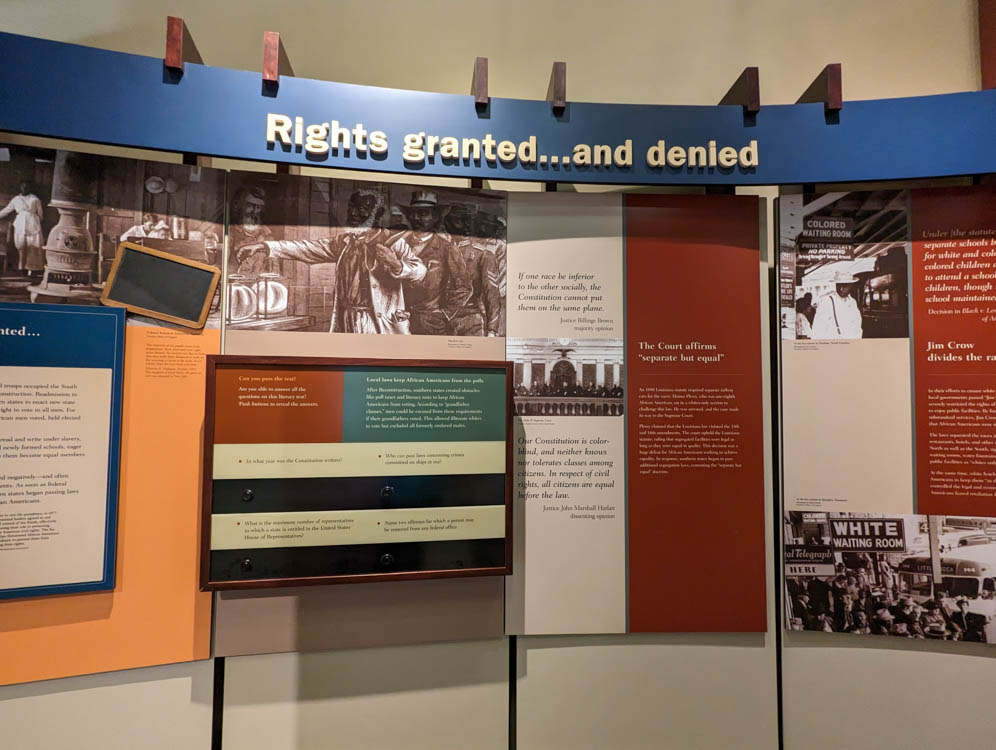

Like most exhibits about the Civil Rights Movement, the museum starts with a section on “how we got here,” “the historic actions on this site” and then “what happened as a result of this action.”

It explains, briefly, enslavement, the Civil War, reconstruction and leads into the time of the Jim Crow laws that were passed in states to restrict the freedoms of black people “legally.” Included in this is the Supreme Court decision of Plessy vs. Ferguson which decided that legally “separate but equal” didn’t affect someone’s constitutional rights to public services. Brown vs. Board of Education said that, at least in public schools, that wasn’t true and therefore schools needed to integrate black and white students together.

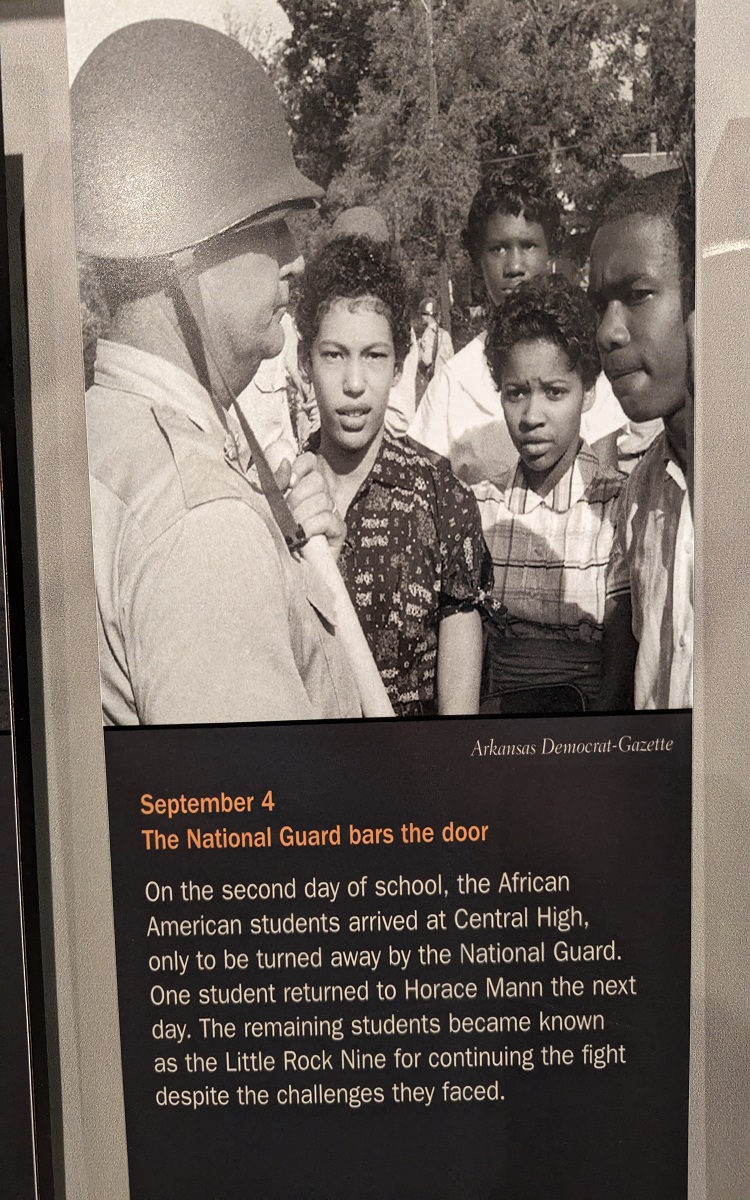

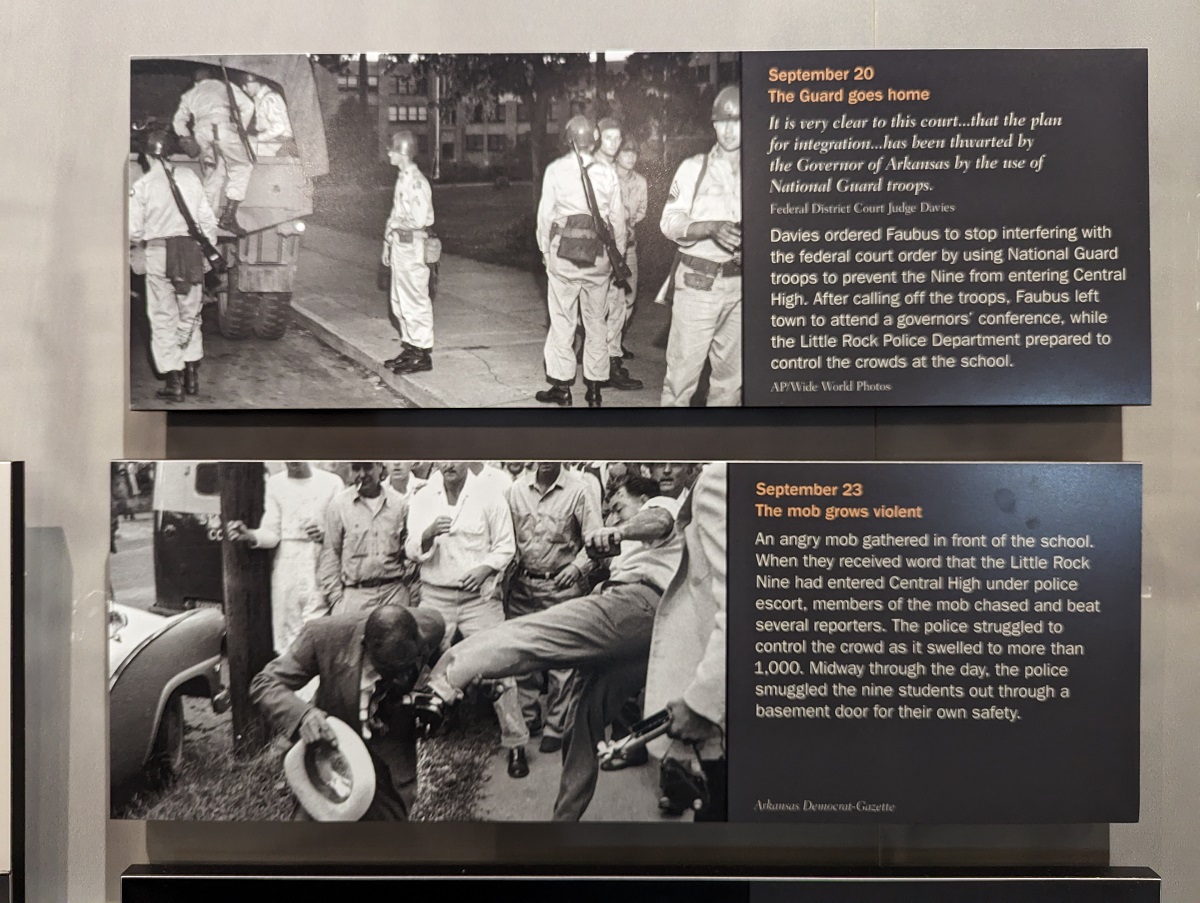

The nine black students of Central High School attempted to attend public high school three times before they were allowed in to learn. The first attempt includes this iconic image which is what’s often associated with any discussion about Central High and what happened that September.

The first attempt was on September 4, 1957. Eight of the nine students got the message that they were going to arrive together to school and be accompanied by ministers and other public officials through the waiting white mob that was sure to come to block their entrance. One student, Elizabeth, didn’t get the message and walked alone through the white mob on the morning of September 4th until she found a bus stop where she sat and waited.

Finally, a local community worker, who was a white, middle aged woman and member of the local NAACP, walked with Elizabeth to help her join her classmates. The Governor of Arkansas, the same from the speech above, called out the National Guard. Not to keep the peace, but to keep the “Little Rock Nine” as they would come to be known, from entering Central High. The students were turned away.

The second attempt came on September 23, 1957 when the Little Rock Nine were ushered into the school through a side door while the Little Rock police, after the President told the Governor he couldn’t use the National Guard to keep students from school, monitored the white mob and journalists out front of the school.

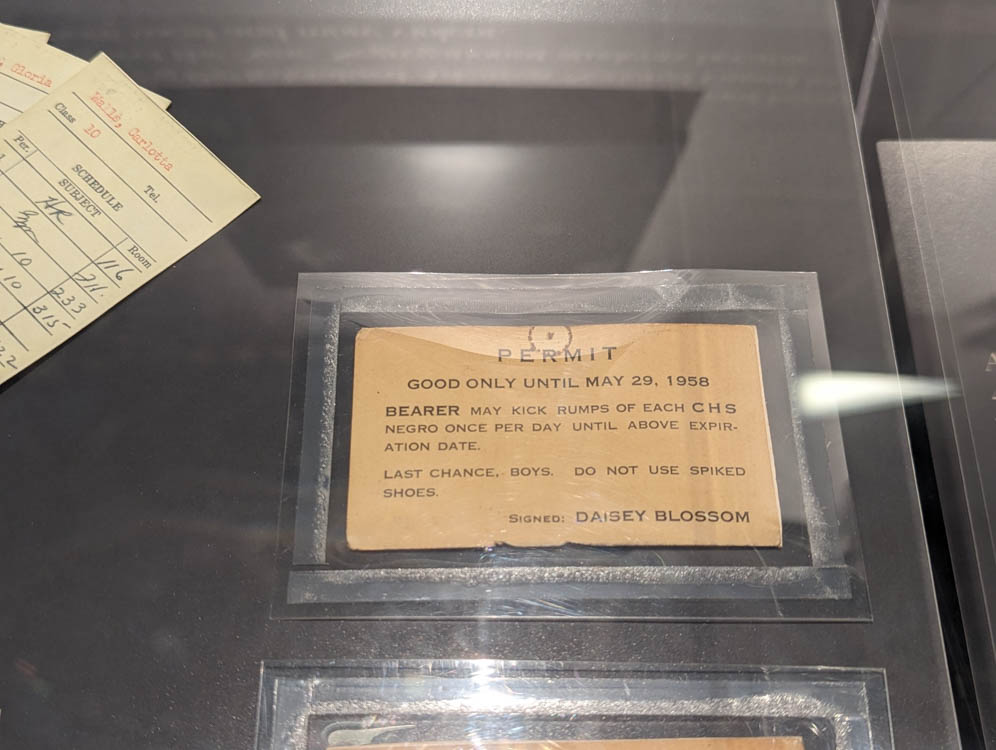

By lunch, as white students walked out of school in protest and told the white mob that the Little Rock Nine were inside, the police ushered the black students into the basement of the school, then into police cars, covered them with blankets and coats and raced out to drive them through the mob. The police couldn’t control the violence that had escalated out front in the morning where the white mob attacked black journalists and were threatening to storm the school to pull out the black students. They asked for school officials to send out “just one to lynch.”

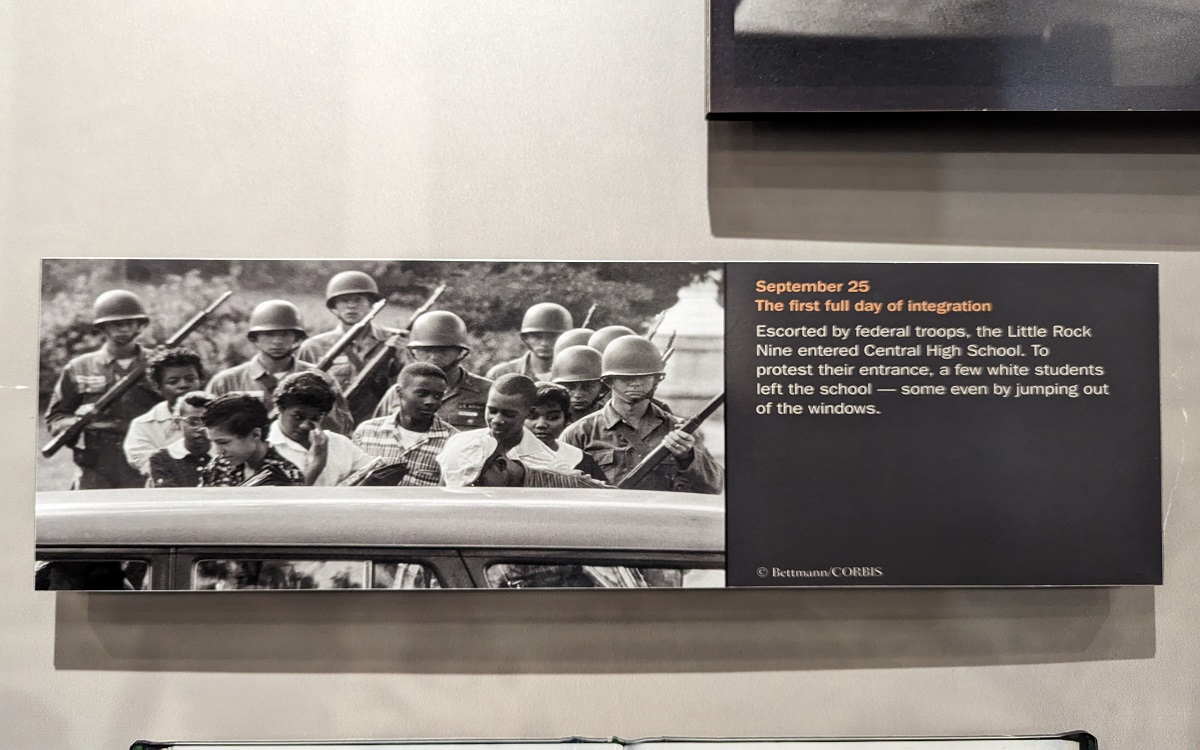

The third, final and successful attempt came on September 25, 1957 when a mobilized army unit from the federal government escorted the students into school and to their classes. As the army weren’t able to go into the bathrooms with the students, a lot of bullying and violence happened to the Little Rock Nine there. While the students were finally able to stay in class, they were still bullied and assaulted throughout the school year. The federal troops were pulled out in November and from December to the end of the school year local troops patrolled the school’s halls.

Ernest Green was the first black student to graduate from Central High School in the spring of 1958 after that hard fought year. Minnijean, one of the nine, was expelled after retaliating against the bullying and violence in school. Rather than allowing the remaining seven to return to an integrated school, the citizens of Little Rock voted in September 1958 to close the public schools. They remained closed for the entire school year. Limited desegregation was voted on in 1959 which reopened the schools, but total integration in the Little Rock school district didn’t occur until 1972.

Standing on the grounds of the school (you’re allowed to go on the grounds outside), it’s easy to be swept back in time and picture what happened that September in 1957. The National Park Service does an excellent job of helping you understand exactly what took place at that intersection, both physically and metaphorically, as black students with quiet dignity insisted on their rights, coming into direct conflict with white racists who were determined to keep them out of Central High School.

The Civil Rights Movement moved on from Central High and expanded over the decades to include Indigenous, other brown and black Americans, the disabled and the LGBTQ+ communities. The battle still continues today to provide a free, fair and equitable society for all Americans.

Leave a Reply